His closest friends and family didn't know how to react to the boy in the white bed, a boy who standing was rarely still or quiet. But this boy hadn't moved a hair.

At 10:30 p.m. that Friday night, Bryan's Volvo hit Brush Creek's pines near 51st Street and Ward Parkway. He was wearing his seat belt when the red R40 side-swiped one tree at approximately 60 mph and then fishtailed into another. The fire department cut him out of the passenger side when they arrived at the scene.

According to Kansas City, Mo. Police Department Captain Rich Lockhart, the most likely cause of the crash was excessive speed, but his family also believes he was on his cell phone or became distracted and simply lost control.

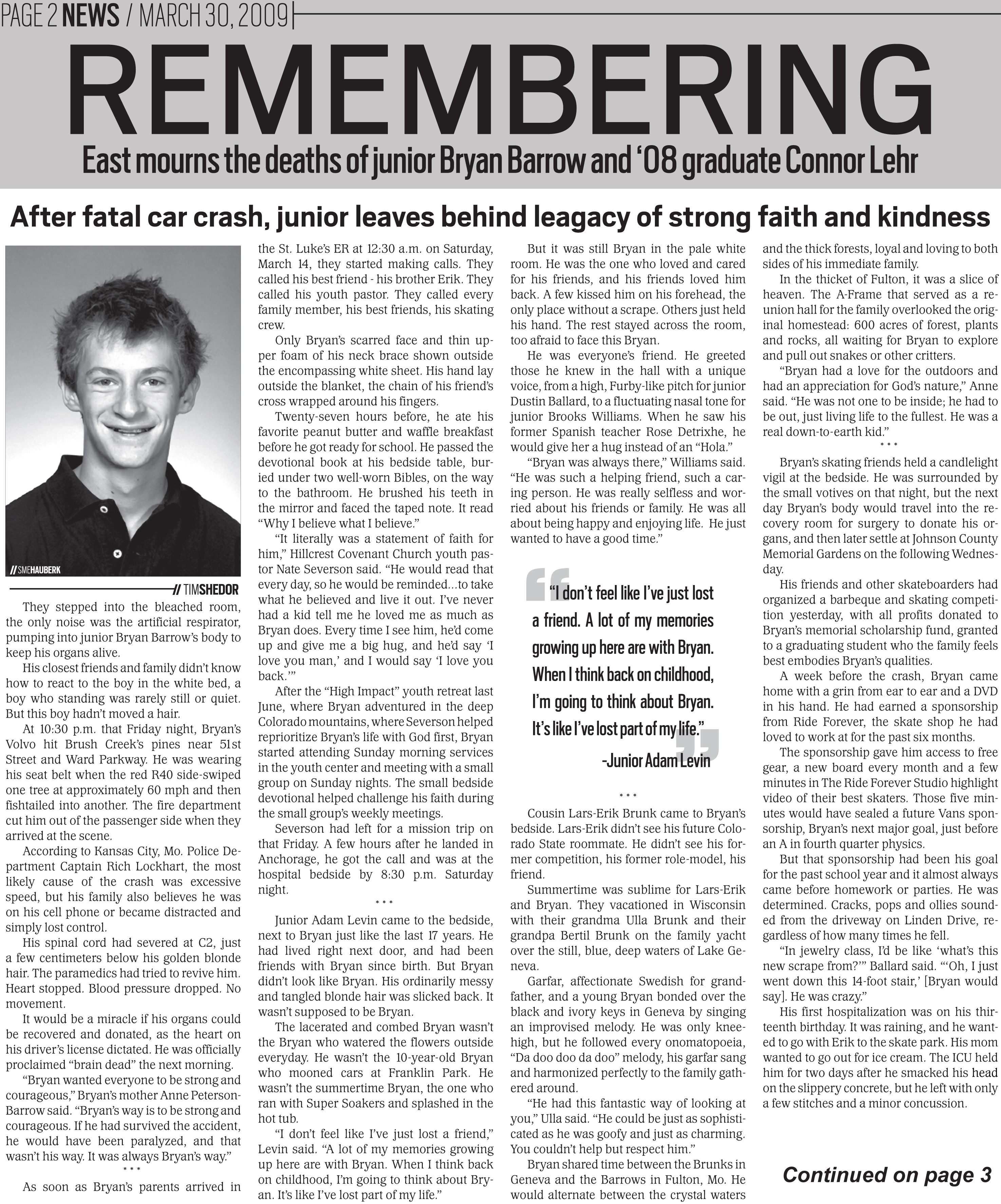

His spinal cord had severed at C2, just a few centimeters below his golden blonde hair. The paramedics had tried to revive him. Heart stopped. Blood pressure dropped. No movement.

It would be a miracle if his organs could be recovered and donated, as the heart on his driver's license dictated. He was officially proclaimed "brain dead" the next morning.

"Bryan wanted everyone to be strong and courageous," Bryan's mother Anne Peterson-Barrow said. "Bryan's way is to be strong and courageous. If he had survived the accident, he would have been paralyzed, and that wasn't his way. It was always Bryan's way."

As soon as Bryan's parents arrived in the St. Luke's ER at 12:30 a.m. on Saturday, March 14, they started making calls. They called his best friend – his brother Erik. They called his youth pastor. They called every family member, his best friends, his skating crew.

Only Bryan's scarred face and thin upper foam of his neck brace shown outside the encompassing white sheet. His hand lay outside the blanket, the chain of his friend's cross wrapped around his fingers.

Twenty-seven hours before, he ate his favorite peanut butter and waffle breakfast before he got ready for school. He passed the devotional book at his bedside table, buried under two well-worn Bibles, on the way to the bathroom. He brushed his teeth in the mirror and faced the taped note. It read "Why I believe what I believe."

"It literally was a statement of faith for him," Hillcrest Covenant Church youth pastor Nate Severson said. "He would read that every day, so he would be reminded…to take what he believed and live it out. I've never had a kid tell me he loved me as much as Bryan does. Every time I see him, he'd come up and give me a big hug, and he'd say 'I love you man,' and I would say 'I love you back.'"

After the "High Impact" youth retreat last June, where Bryan adventured in the deep Colorado mountains, where Severson helped reprioritize Bryan's life with God first, Bryan started attending Sunday morning services in the youth center and meeting with a small group on Sunday nights. The small bedside devotional helped challenge his faith during the small group's weekly meetings.

Severson had left for a mission trip on that Friday. A few hours after he landed in Anchorage, he got the call and was at the hospital bedside by 8:30 p.m. Saturday night.

Junior Adam Levin came to the bedside, next to Bryan just like the last 17 years. He had lived right next door, and had been friends with Bryan since birth. But Bryan didn't look like Bryan. His ordinarily messy and tangled blonde hair was slicked back. It wasn't supposed to be Bryan.

The lacerated and combed Bryan wasn't the Bryan who watered the flowers outside everyday. He wasn't the 10-year-old Bryan who mooned cars at Franklin Park. He wasn't the summertime Bryan, the one who ran with Super Soakers and splashed in the hot tub.

"I don't feel like I've just lost a friend," Levin said. "A lot of my memories growing up here are with Bryan. When I think back on childhood, I'm going to think about Bryan. It's like I've lost part of my life."

But it was still Bryan in the pale white room. He was the one who loved and cared for his friends, and his friends loved him back. A few kissed him on his forehead, the only place without a scrape. Others just held his hand. The rest stayed across the room, too afraid to face this Bryan.

He was everyone's friend. He greeted those he knew in the hall with a unique voice, from a high, Furby-like pitch for junior Dustin Ballard, to a fluctuating nasal tone for junior Brooks Williams. When he saw his former Spanish teacher Rose Detrixhe, he would give her a hug instead of an "Hola."

"Bryan was always there," Williams said. "He was such a helping friend, such a caring person. He was really selfless and worried about his friends or family. He was all about being happy and enjoying life. He just wanted to have a good time."

Cousin Lars-Erik Brunk came to Bryan's bedside. Lars-Erik didn't see his future Colorado State roommate. He didn't see his former competition, his former role-model, his friend.

Summertime was sublime for Lars-Erik and Bryan. They vacationed in Wisconsin with their grandma Ulla Brunk and their grandpa Bertil Brunk on the family yacht over the still, blue, deep waters of Lake Geneva.

Garfar, affectionate Swedish for grandfather, and a young Bryan bonded over the black and ivory keys in Geneva by singing an improvised melody. He was only knee-high, but he followed every onomatopoeia, "Da doo doo da doo" melody, his garfar sang and harmonized perfectly to the family gathered around.

"He had this fantastic way of looking at you," Ulla said. "He could be just as sophisticated as he was goofy and just as charming. You couldn't help but respect him."

Bryan shared time between the Brunks in Geneva and the Barrows in Fulton, Mo. He would alternate between the crystal waters and the thick forests, loyal and loving to both sides of his immediate family.

In the thicket of Fulton, it was a slice of heaven. The A-Frame that served as a reunion hall for the family overlooked the original homestead: 600 acres of forest, plants and rocks, all waiting for Bryan to explore and pull out snakes or other critters.

"Bryan had a love for the outdoors and had an appreciation for God's nature," Anne said. "He was not one to be inside; he had to be out, just living life to the fullest. He was a real down-to-earth kid."

Bryan's skating friends held a candlelight vigil at the bedside. He was surrounded by the small votives on that night, but the next day Bryan's body would travel into the recovery room for surgery to donate his organs, and then later settle at Johnson County Memorial Gardens on the following Wednesday.

His friends and other skateboarders had organized a barbeque and skating competition yesterday, with all profits donated to Bryan's memorial scholarship fund, granted to a graduating student who the family feels best embodies Bryan's qualities.

A week before the crash, Bryan came home with a grin from ear to ear and a DVD in his hand. He had earned a sponsorship from Ride Forever, the skate shop he had loved to work at for the past six months.

The sponsorship gave him access to free gear, a new board every month and a few minutes in The Ride Forever Studio highlight video of their best skaters. Those five minutes would have sealed a future Vans sponsorship, Bryan's next major goal, just before an A in fourth quarter physics.

But that sponsorship had been his goal for the past school year and it almost always came before homework or parties. He was determined. Cracks, pops and ollies sounded from the driveway on Linden Drive, regardless of how many times he fell.

"In jewelry class, I'd be like 'what's this new scrape from?'" Ballard said. "'Oh, I just went down this 14-foot stair,' [Bryan would say]. He was crazy."

His first hospitalization was on his thirteenth birthday. It was raining, and he wanted to go with Erik to the skate park. His mom wanted to go out for ice cream. The ICU held him for two days after he smacked his head on the slippery concrete, but he left with only a few stitches and a minor concussion.

"In the ambulance on the way to Children's Mercy, I thought to myself 'I hope I never have to go through this again," Anne said. "I worried about him all the time when he was out skateboarding, or doing anything."

Even when he wasn't on his board, he was a natural athlete and played soccer for East during his three year high school career. His cleats moved like a dancer's feet; it was like he was choreographed. A lucky fan would be able to glimpse his mouth, biting down on his tongue in determination, just like he'd done since preschool. Next season will be dedicated to Bryan and his legacy of fancy footwork on the grass.

"He had this smile," head soccer coach Jaime Kelly said. "And whenever you saw this smile….it always kind of made you laugh and bring a smile to your face."

Before Bryan's gurney moved down the hall, his family and friends held hands around the white, suddenly warm room. Severson led the prayer, hoping for a miracle that Bryan's organs could be donated despite his condition and the doctor's forebodings.

His garfar sang "Tryggare Re Kan Ingen Vara," the Swedish hymn "Children of the Heavenly Father," as his last parting "Do do da da do do do." The rest took turns saying their last good-byes, Bryan's dad, Bruce, leaning in closely to tell him which friend was coming next.

"I just walked in, and you gotta take deep breaths before you walk into that room, because you can't control tears from coming out of your eyes when you walk in there and see your best friend lying on the bed, completely, just gone," Levin said. "There's no way to describe that feeling. I didn't know what to say. I had to sit there for a few minutes and just look at him. Held his hand, and touched him, and finally, I don't even remember what I said. I said good-bye and told him I loved him and then I left. I can't even remember what I said to him, it's just overwhelming to see that."

The doctors' return from the recovery room came with the bittersweet news. They were able to save each organ and find a needy body. His liver was going to a 60-year-old. His first kidney to a 57-year-old, his second to a 52-year-old. His pancreas: a 45-year-old. His heart was going to a 22-year-old who would have only had a few days left to live.

Bryan was the boy who gave everything, from a sympathetic ear for his friends to love and loyalty for his closest to a few vital organs for strangers. He couldn't return the "I love you's" and forehead kisses, but he didn't need to.

"It struck me a couple days ago…he only got to live 17 years," Severson said. "And then I thought, 'He got to live 17 years.' And I was thankful God let me be a part of that. He got 17 years and he lived it to the fullest and I guarantee he's got no regrets."